Steak, Grief, and Loss

Exploring how Korean BBQ aligned with my understanding of grief and loss. (I know, I know. Read on to see how it all connects!)

I don’t like steak.

That’s not the same as not loving beef. Put it in a stew, minced and seasoned in a taco or sauteed in a savory teriyaki sauce, and I’ll go for seconds. I love it in the form of a roast with some carrots and smothered in gravy or ribs braised slowly in a Dutch oven… Delicious.

But place a whole slab of red, bleeding flesh on a plate in front of me and my cheeks will puff out from an involuntary gag reflex.

I don’t like steak.

Before you try to convince me, I get it. I’ve had the most tender pieces of Kobe beef from the tasting menus of celebrity chefs along both coasts. I’ve watched every man in my life throw it on a grill in the summer or pan sear it during a cozy autumn, spooning butter over it as it sizzles, closing their eyes with pleasure as they chew.

Many have tried - each confident they could be the one to turn me - and failed.

Even when it melts in my mouth, I can’t rid myself of the sensation that I’m eating a chewy piece of flesh.

It’s not logical. It’s emotional.

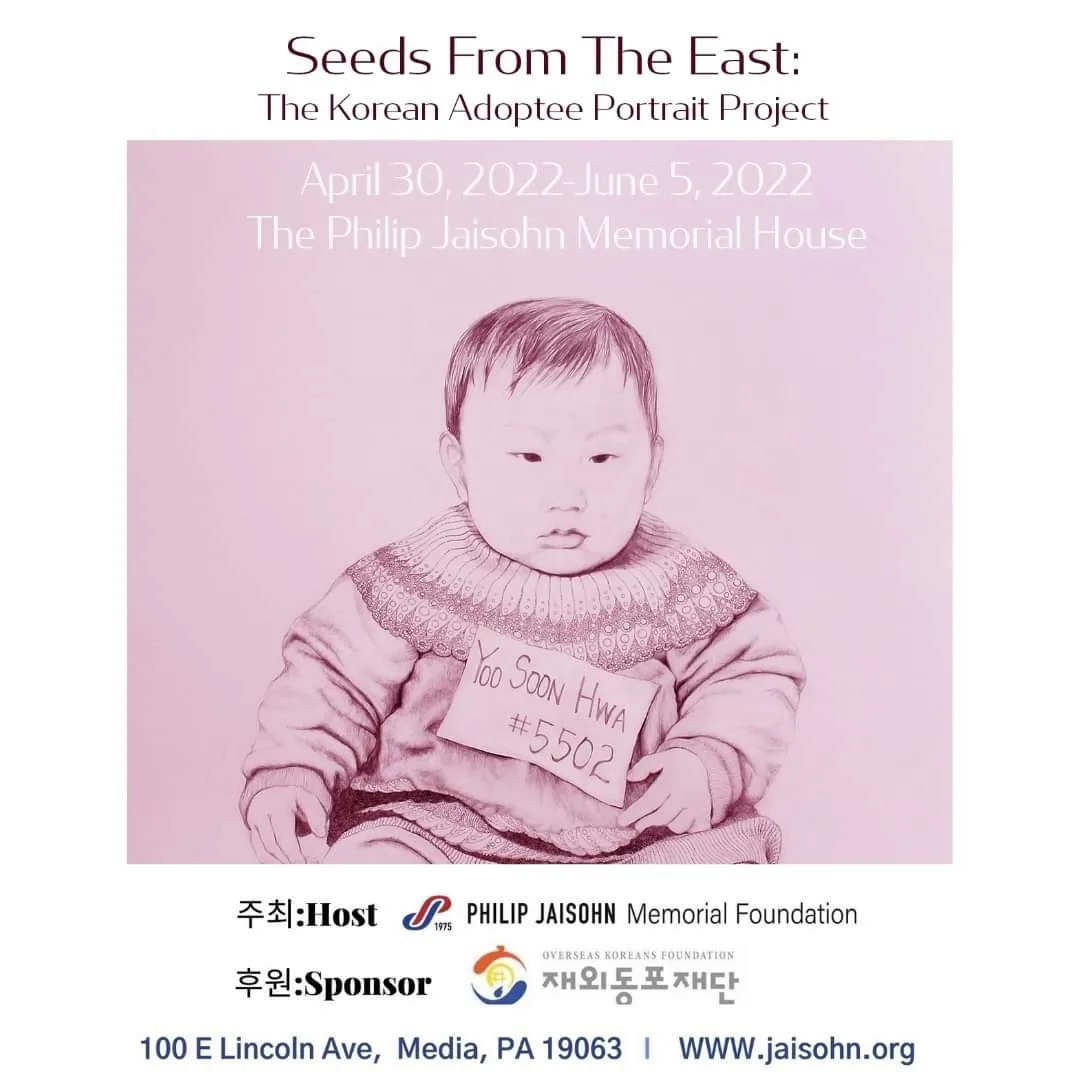

I don’t remember the first time I became aware of Korean barbeque, but I do remember the first time I tried it. It was in the Philadelphia suburbs. The local Dr. Philip Jaisohn house (integral in the Korean independence movement in the States, he was the first ever official Korean American. The house he resided in with his wife and children is now a museum in Media, PA) had hosted my now-friend AD with her moving, emotional, and stunning exhibit entitled Seeds of the East: The Korean Adoptee Portrait Project.

The exhibit featured 12 Holt International Korean adoptees AD took the care to learn about so she could bring life and beauty to their origin stories. She transformed their tiny, 2x3 inch black and white adoption agency ID pictures into life-size, vibrant, and personalized recreations.

Having just entered the scene of the greater Philadelphia Korean American community, I was asked to introduce AD at the official opening of her exhibit. I readily agreed.

Though truthfully, I had no idea what to say as an introduction, what her work would come to mean to me, where this journey of exploring Korea and my adoption story would lead, and how often I would end up looking back on that evening over the next three years.

My friend, Melissa, fellow Korean adoptee, was one of the individuals highlighted in AD’s work.

We went together to the opening and would later take our moms to see it on Mother’s Day, the kind people who oversee the grounds opening it just for us that morning.

“I read online that the artist feels like her parents stole her from her culture,” my mom said before we left. Pointedly, she said to me, “I hope you don’t feel that way about us.”

A statement, not a question.

My nervous system detected and automatically reacted to the layer of preemptive hurt and discouragement in her tone, brimming just below the surface of her words. I immediately acquiesced. I have always felt a protectiveness of my mom and an impulse to consider her feelings first. Of course I didn’t feel that way.

Truthfully, I never thought much about Korea at all.

Some subconscious part of me thought: there must be a reason that, growing up, I didn’t see people like me on television. It must not be worth knowing or exploring further.

And I had a great life filled with lots of love and opportunities. I had a happy childhood. She didn’t have to worry about me feeling as if she’d stolen me from anywhere, least of all a country and culture I didn’t know about.

Truthfully, I never thought much about Korea at all.

My general life philosophy leads me to understand that everyone has a different experience and relationship with a topic which I can validate and value without having to take on as my own. So, while, at that time, I acknowledged AD’s words about feeling grief and a loss about not growing up in Korea, about missing out on an opportunity to know a culture because of adoption, I listened.

And I dismissed the notion with my entire being.

Grief?

Loss?

How could she grieve something she had never known or experienced?

Over the coming months, words like “grief,” “mourning,” “loss,” “healing,” and “trauma” would stand out to me from adoption forums and interviews like neon lights on a page, shouting at me as if through a bullhorn in a private theater.

I began to notice it immediately after seeing AD’s work that night.

But I still didn’t understand the weight of these heavy words. We could always visit Korea - as I was going to do with Melissa that coming summer - and read about the culture the same as any other in the world. It didn’t mean I was upset about not growing up there.

Anything I knew about Korea felt so foreign and abstract. I once had a coloring book filled with realistic cartoons of Korean kids playing games and of women carrying water wearing traditional hanbok, and couples at a vibrant and colorful wedding ceremony. It may as well have been a different world let alone a country where I was born.

I especially didn’t like the tough, stringy, chewy bulgogi - a popular marinated Korean beef dish - they’d made for us at culture camp when I was in middle school during the 1990s. It had been my first and only impression of Korean food.

In my mouth, it felt like reheated-in-the-microwave, leftover, over-cooked cuts of London broil. I made a snap judgement and didn’t seek out other examples of Korean food after trying this one poorly made, mass produced dish at a heritage camp in the middle of the woods in New Jersey.

Instead, each year, in the late 90s, my parents picked me up from camp with an Italian hoagie so I wouldn’t have to eat the “special” final meal we had prepared all week for our families.

The night I met AD, I wore a pale yellow dress and said all of the right things to introduce her and her work in 2022. She sat and looked at me thoughtfully behind smart, dark-framed glasses while wearing a great skirt. She proceeded to talk about the inspiration for her work, the process, the research, and the meaning behind the floral designs and love she instilled into each piece.

As she spoke, something inside of me - something I couldn’t yet identify, was beginning to melt.

An animated carousel of books popped up on the screen of her presentation. These are the books I read as research before beginning the project, she said. Some were about Korean war history and others were memoirs or research books about intercountry adoption. Knowing nothing about art or the artistic process, I listened and wondered how knowing about Korean history would help her draw a recreation of a small photograph.

I approached her afterwards, wondering out loud if she could send me a link to the books she had read. She agreed readily. With a somber tone in her voice, she added a verbal note that stuck with me like a barnacle to the side of my brain.

I had to recover after reading each one.

As she spoke, something inside of me - something I couldn’t yet identify, was beginning to melt.

My ears perked up and filed away the sentence for a later time. Said as a matter-of-fact: I had to recover after reading each one. Every fiber of my being believed and accepted the words uttered with thick and serious sorrow in her voice. But it was not yet possible for my heart and brain to catch up and fully comprehend them.

I couldn’t fathom the depth of her meaning.

It would be weeks - weeks that rolled into months - before I began to understand the emotional toll of the learning process. Learning about our country of origin, the centuries of struggle, war, occupation, poverty, separation, displacement, abuse, and heartaches of the people and the place where we were born came the sudden acknowledgement of a culture we will never quite know as intimately as if we had lived in it … Once I began the journey of uncovering each morsel of a fact and topic, it gradually accumulated around my heart. Some of it rubbish. Much of it gold. And all of it adding to the very real grief it is possible to feel after you begin to see parts of your Self that you never knew existed.

Several months later, after spending three weeks in Korea with Melissa and 30 other adoptees from around the world… after meeting my birth father, my half sister, and an aunt, after sitting in the children’s home where he dropped me off almost 40 years prior, and paging through the time capsule of records he had left back then, after walking on the streets of the seaport city where I was born, after looking out into the Yellow Sea from the cliffs of Jeju Island, wild horses adorning the greenery behind me… it was only then that I began to truly embrace AD’s meaning.

… Once I began the journey of uncovering each morsel of a fact and topic, it gradually accumulated around my heart. Some of it rubbish. Much of it gold. And all of it adding to the very real grief it is possible to feel after you begin to see parts of your Self that you never knew existed.

I was double booked the night of AD’s exhibit opening. When she, Melissa, and Melissa’s daughter invited me to join them for a meal of Korean barbecue, I canceled my appearance at whatever it was I was supposed to do back in my borough, sensing that this dinner, with these women, in this time was something invaluable. A clue. Part of the bigger picture.

I was right.

We walked into the dark restaurant with the bright, gaudy Korean BBQ sign outside. The floors were cement and thick silver tubes hung down in the center of each table over a round grill top. I had never seen anything like it.

My heart sank a bit when the server brought over a tray of thick slabs of beef. I eyed the colorful bowls of various kimchi and sprouts, lettuce, and sauces, garlic and thinly shaved onions in red sauce, presented in small bowls. They were completely foreign to me.

Someone went to work pouring us tiny glasses of apple flavored soju. It looked like a wine cooler and tasted like one, too. My first experience with it, I had little idea that the flavors are more popular in America, that Koreans drink it by the bottle without any flavoring at all. That sometimes they drop a shot into a glass of light beer and call it somaek (soju and maekju - the Korean word for beer). I didn’t know that within a few years, I would be doing the opposite when sitting around a Korean BBQ table in Seoul with family or friends: drinking soju by the glass, a splash of beer to take the edge off the harsh bite of alcohol I enjoyed in the sugar-free varieties.

The server came by to pick up the slab of meat with some serious-looking tongs, a pleasant aroma sizzling from the grated grill in front of us, smoke being sucked up by the cylindrical tube from the ceiling. She used scissors to cut the beef into bite-size pieces, putting the cooked ones off to the side.

I was raised to be polite. And, I was also starving. So, I popped a piece of grilled beef in my mouth.

I expected to chew.

For a long time.

But the tender, savory, delicious texture of the meat all but melted before my teeth could make contact with it. Watching AD, Melissa, and Katelyn navigate their way around the table, I copied their movements, grabbing a piece of lettuce with my chopsticks, adding beef, the thick red paste (ssamjang), soy sauce soaked strips of green onion, a sliver of raw garlic, and a piece of kimchi on top, wrapping it up as the most perfect bite, and then devouring it. The bright acid crunch of the kimchi, the umami of the bean paste, the tang of the garlic and sweetness of the onion, the savory chew of the beef… Never had I experienced such variety and comfort in a single bite.

We sat and chatted, all of us being a bit less formal than we had been at the gallery opening.

AD watched me from the side of her eye in between sips and bites.

Never had I experienced such variety and comfort in a single bite.

And she knew.

She knew the same way that *I* now sometimes know when I share my story with others.

She knew I didn’t understand what she meant by the depth of meaning and sorrow behind each piece of art she crafted for our adoptee peers after hearing their stories.

She knew I was about to enter a complex, heartbreaking, joyous kaleidoscope of confusion while unearthing - in tender, sometimes bitter bite-size pieces - modern Korean history about war. Occupation. Resulting orphans. Racism. Poverty. Traditional family structures. Money. Greed. Coercion. Lies. Corruption. Sexism. And all of the outcomes from a tumultuous cocktail of pain, heartache, pride, and turmoil of a tiny country fighting for its independence, its culture, and its people while systematically sending away its children.

And we - the children - now grown and beginning to understand that we have missed out on some portion of a life knowing about soju, kimchi, shared meals around a bapsang, customs, music, clothing, traditions, history, language, books, movies, friends, and families.

The past three years have opened my eyes to so much.

I had a happy childhood. And I love my family. And I have complex feelings about catching up on the culture I missed out on as a result of not growing up in Korea.

Being in Korea is restoring some of the soul I didn’t know I had.

And now, I love steak.

Note: Please follow AD Herzel’s work on LinkedIn or on Medium.

If you have questions or comments, leave them here! I will address them - “unplugged” and unscripted - on my Spotify podcast: Exploring with Jenna Lee Kim. Stay tuned, and thanks for exploring along with me.

I feel honored to bear witness to the awakening of your soul. The amount of learning you have pursued in the past few years and the emotional labor you have bravely chosen are priceless ❤️