I remember the day I spied two women pushing strollers on the sidewalk running along the front of my house in the borough in Pennsylvania.

I left my son safely on his blanket on the floor and sprinted out the door to greet them. I must have looked like a sight: barefoot, tiny shorts, oversized shirt, probably bra-less, moppy hair, and then the words coming out of my breathless mouth: “Hi! Are you stay-at-home-moms?!”

The two women were gracious, explaining that they weren’t. They were nannies, but I should try meeting up with other moms and caregivers at the borough library. They take a lot of walks, however, so perhaps we could meet up one day.

I never noticed them walking by my house again.

The days dragged on and I dug deeply into the recesses of my few natural talents: striking up conversations with strangers.

When I saw Emily, I was like a detective putting together the pieces.

Who: A mother of a baby.

What: A baby older than 3 months old, which meant if the mother was intending to go back to the traditional workforce, she probably would have by now.

Where: Kohl’s Department Store on a Tuesday, late morning.

When: A work day.

Leaving the traditional workplace to be my son’s primary caretaker was, like everything else in life, not exactly what I was expecting.

We made small talk for a bit, and when I watched her walk away, my heart pounding as it sank slowly into my stomach with her every step, I knew I’d regret it if I didn’t act.

I hurried after her.

“Hi! I’m sorry. (Women are always apologizing.) I hope you don’t think I’m crazy. (...And being self-deprecating to humble themselves to others. Can’t we simply be direct without the impulse to preface or over explain our desires and needs?) Are you a stay at home mom? Because I am. And if you ever want to get together with our babies, here’s my number…”

Eight years, three more babies, one new house, and a move to Korea later, Emily is one of my best friends. We chat every day through video messages and funny reels from social media. She is a lifeline for my constant need for external processing, emotional validation, and a safe place to land when I need a non-judgmental ear, shoulder, and sometimes, just good old-fashioned conversation and love.

Leaving the traditional workplace to be my son’s primary caretaker was, like everything else in life, not exactly what I was expecting. I found myself running up against so many truths and realizations that probably should have been obvious, but - simply - were not until I was experiencing them firsthand.

Like: If you’re achievement-oriented and your 60-hour-a-week office life has suddenly stopped, you find yourself at an abrupt transition. There are a lot of hours in a day when you have a baby who sleeps well and wakes up at 6:30 in the morning.

I’ll state the obvious: I love my kids in an all-encompassing way. And when you’re a “big E,” as they say in Korea: a true extrovert who is energized by the stimulation of conversations, human interaction and connection, and requires people for survival in the same way that one needs water and sleep… When you’re like this, having only the company of a baby for days at a time is a challenge.

I would no longer be tethered. My oxygen tank would need to be replenished. What would be my proverbial “purpose”?

Before we made the decision to move to Korea, it occurred to me that I was doing it again:

I was actively transitioning to a new type of isolation, the same as I inadvertently did when I left my career to stay home with our son.

Only this time, I was moving to a literal island in a different hemisphere where I not only wouldn’t have a job, I wouldn’t be able to speak the language, and would - in effect - also be leaving every single support person, friend, family member, loved one, resource, and connection, including my therapist.

I would no longer be tethered. My oxygen tank would need to be replenished. What would be my proverbial “purpose”?

18 months into living in Korea, I am indeed on an island. I find myself in a world where the natural skills I have are worthless, like a cell phone that can’t hold a charge or a coffee pot without any beans.

I have limited knowledge of the programs or resources here to feel capable. I can’t rely on language skills for emotional or practical survival. Even ordering something online takes 6 to 8 screenshots and sending them to someone who knows Korean. (Shout out to every patient and wonderful friend who helps me on a daily basis!)

Here’s what I do have: a car, a license, a laptop, a translating app, a smile, and a bit of intuition.

I tutor some Korean adults in a conversational English class. My only real qualification is that I’m a native English speaker. Currently, it’s my only source of steady income. It’s also unreliable. Often, my students decide they are too busy, that they’re not learning anything, or my class is simply not a priority for them.

And I’m back to scrambling for a way to pay my rent.

Already, these women felt like aunties or close neighbors I have known my entire life.

So, I drive 45 minutes one way to a class that a Korean friend of mine graciously put together for me with four lovely adult students who each pay the equivalent of $20 a class to join me for an hour and a half each week.

One morning, after dropping the kids off at school, I was on my way to meet them. With a bit of time to spare, I pulled into the driveway of a cafe I had noticed the week before. Colorful banners with photographs of western sandwiches, muffins, and cast iron pans of shrimp decorated the picture windows. A sandwich board outside showed a drawing of a coffee cup and the words “Take Out” beneath it.

The marketing was on point.

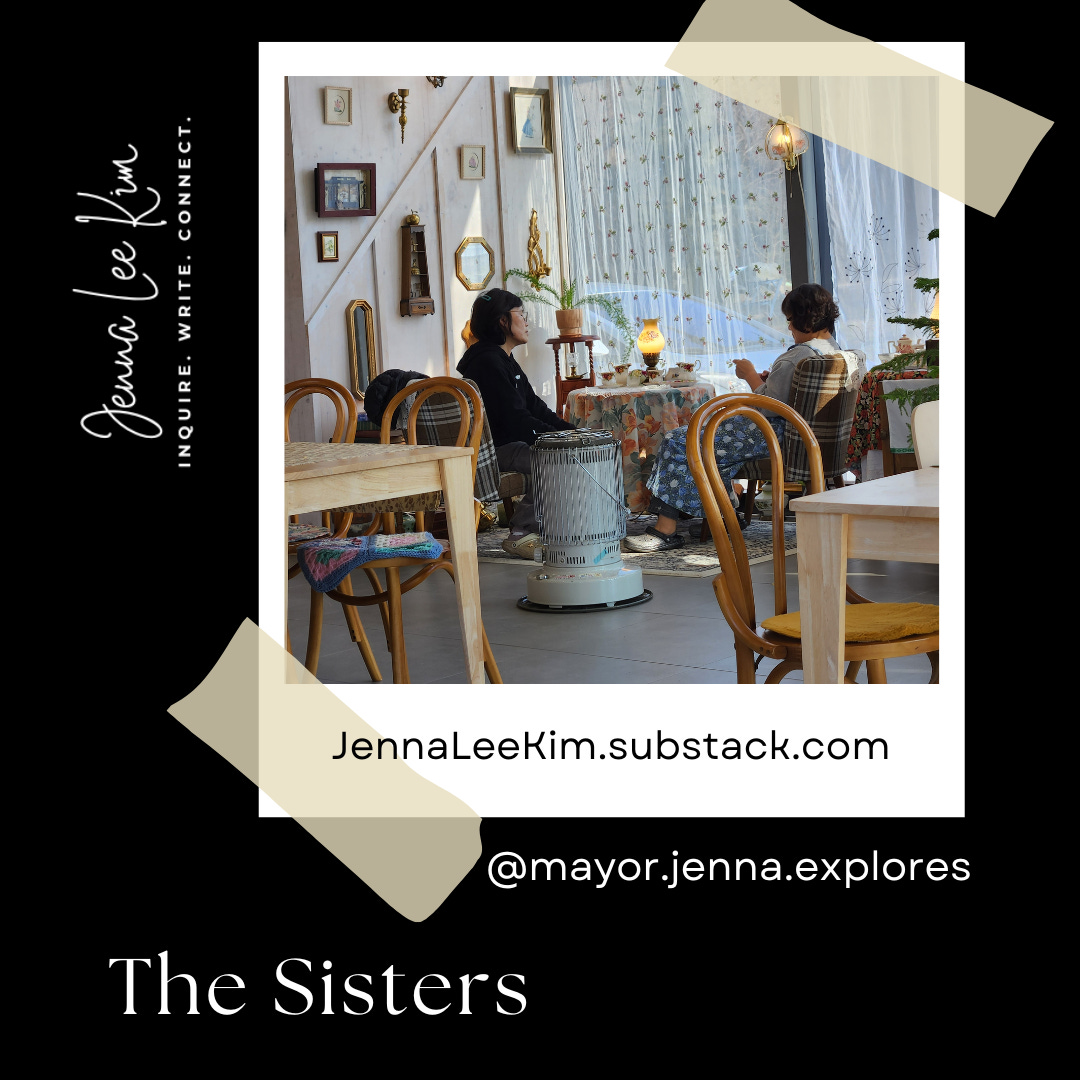

I opened the door to the bright and inviting space. I spied an open kitchen window in the back - common in Korean restaurants - floral tablecloths, and vintage, English-style porcelain plates with teacups and saucers decorating one side of the restaurant.

“Aha! Ann-yeong-ha-sey-o!” A Korean woman with dark-framed glasses walked toward me. Another appeared and stood behind the counter. Something about their mannerisms and the tilt of their heads when they spoke, their bright voices, and inviting smiles seemed similar and so natural that they were familiar to me though they were strangers.

When I’m speaking to Koreans, I’m like a marionette, putting on a one-woman show.

I ordered an oat milk latte for 4,000 won, about $2.75. I bowed and thanked them in Korean - Gahm-sa-hab-ni-da - before I walked away.

The latte was nutty and delicious.

The next week, I stopped by again, and the two women recognized me, approaching with enthusiasm, and this time holding up hands to take both of mine in theirs, pulling me in for an embrace that felt naturally maternal.

This physical act of welcome may seem commonplace for a westerner, but it is not typical for a Korean. Already, these women felt like aunties or close neighbors I have known my entire life.

In a personal chapter of constant uncertainty, I suddenly felt cozy and protected, like I belonged there with them in that brunch cafe.

“Where are you from?” The woman with the glasses asked me with curiosity.

“Mi-guk im-nida,” I responded. I am American. One of the only sentences I can manage to utter in Hangul.

“Ahh-ha!” She said. “You are teacher?”

I smiled, “Ne!” I spoke slowly and with inflection, the way I had learned to do when conversing with novice English speakers. “I teach English to adults!” I took my hand, palm down, and raised it when I said ‘adults.’

When I’m speaking to Koreans, I’m like a marionette, putting on a one-woman show, using every expressive and conversational skill in my toolkit to convey my thoughts in an effort to communicate.

“Oh!” she exclaimed. She glanced at the other woman.

“Teach us? I want learn English,” she said. She initiated putting her number into my phone. “Ava,” she said, pointing to herself. “My sister, Sharona,” she said, gesturing to the other woman.

Sisters! Of course. I now saw the similarities in their faces and mannerisms.

English, as a language, is difficult. When you’re communicating with non-native speakers, you must be careful to use simple sentences, as few words as possible, and ones that have exactly one meaning.

After my morning class, I returned to the sisters’ brunch cafe at noon. I looked at their menu and ordered freshly made pappardelle with lemon, garlic, oil, grated parmesan, a side salad, and a piece of crusty bread… I supposed I would begin my gluten-free diet the next day.

We worked through the details of the class. Date. Time. Cost.

Later, Ava would send a message that said, “Everything you eat at our cafe is free.”

After we decided on a lesson schedule to begin the following week, I settled myself into a corner of the cafe close to an outlet and pulled out my laptop.

I watched out of the corner of my eye as they busied themselves in the kitchen. The only other customers who appeared that afternoon were two men with a pickup truck and their pet dogs in the bed of it. I heard some discussion and chatter with the sisters. A bit later, they left carrying drinks and brown bags filled with baked goods.

Ava hurried over. “Jenna!” she said. “Will you try some iced chocolate?”

Thinking she meant ice cream, I wistfully thought to myself, “I suppose I’ll start my non-sugar diet tomorrow.” I followed her toward the kitchen. Sharona was busy pouring chocolate syrup into a cup of milk and ice.

“Men ask for chocolate. No caffeine,” Ava said. I looked at her with a scrunched brow.

“Do you mean a chocolate latte? No coffee?” She nodded. “I don’t charge them. Try it. See if it is good!”

I did. And it was.

“Basically, they wanted a chocolate milk,” I thought to myself, sipping the sweet, cold drink.

As if I had said this out loud (I hadn’t), Ava looked at me and shook her head with a small, sly smile. “Men. Babies,” she said.

If it was a sitcom, I would have done a proper spit take or milk would have shot out of my nose. I guffawed, a proper laugh from my belly. It wasn’t what she had said so much as the fun of her voicing a kind of sentiment I had been thinking at the same time.

Our purpose in that moment wasn’t to disparage men. A Korean ajumma in her early 60s, used her limited English to connect with an American, knowing it would make me laugh.

The next week, I returned. We sat together with an English workbook, my laptop, and all the time in the world. I ordered a hot Americana. I showed them pictures of my kids. I explained that their dad and I are friends but no longer together. They told me about their siblings, about studying cooking in the Mediterranean, attending university in Seoul, that they have kids, Ava has grandkids, and they run an AirBnB with their husbands. With our limited language skills, we made each other laugh with jokes about marriage, kids, and oohed and aahed over one another’s family pictures.

They were astounded by the story of how I found my Korean family, looking on with curiosity and genuine care, asking questions as I showed pictures of my Appa, my sister, my brother and our Omma, and my niece.

The week after that, I arrived at the cafe and Ava hurried over for a hug. “Did you eat lunch?” she asked. “Oh, no!” I said and moved toward the counter to look at the menu.

Ava motioned for me to sit down. “We make curry,” she said. She brought over a plate of cubed potatoes, carrots, broccoli, and a chicken wing smothered in a yellow curry sauce, set next to a pile of purple rice. Soon, they joined me at the table. “We will eat,” Sharona said. I set down my fork, understanding my error and sensing what was next.

The sisters bowed their heads and were silent. I watched them as they prayed, adoring them the same as I would adore my own mother, and when they looked up in unison, they saw me watching them and both smiled.

Each week, we sit together at a table at their brunch cafe north of the island, close to the sea. They feed me lunch. They make me an oat milk latte. Our lesson is interrupted by customers, but as I have nowhere to be, I don’t mind. I sit in the corner of the cafe, and after our lesson, when they declare that they are tired of learning for the day, I write. They bring me tea. Or a bag of tangerines. Or, if they feel I’ve gone too long without food, invite me to eat kimchi jigae or gimbap with their friends. They show me around their home just behind the cafe. They’ve decorated with western antiques from England or the United States.

These sisters, who grew up in Daegu and have siblings and kids all over Korea and in China, moved to Jeju Island a year before we met.

They took a chance by striking up a conversation with a stranger: a struggling, often lonely foreigner living in Korea.

Stopping by that cafe on a whim is one of the best decisions I made since moving to Korea.

They breathed oxygen into my life.

And I will forever be grateful for the sisters.

Questions? Comments? Leave a comment here and I’ll respond to it on my Spotify Podcast: Exploring with Jenna Lee Kim in an “unplugged” and unscripted way! You can also email me at jenna.tae.hee.kim@gmail.com

This is a lovely story and relationship you share with the sisters. And completely off topic, but 100 percent correct observation by you and the sisters: I am that man baby.

If I am ever on Jeju Island I will insist on meeting Ava and Sharona! Like the characters in a well-written novel, I feel like I know them and find myself thinking about them long after I finished your essay.